Showing posts with label vitalism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label vitalism. Show all posts

18.11.18

Tienes alma; acéptalo y deja de joder

Tienes alma; sí, estás viva.

Si estás viva, tienes alma.

Dá lo mismo cómo.

¿De dónde sacas que te fue entregada,

estirpada de quien mereces un perdón

por un perdonable nunca presente

enmascarando tu soledad fingiendo serle?

¿Así ya no te sientes insuficiente

porque no puedes comprender qué es dar a luz?

¿Cómo te engañas que computa ese trueque;

acaso se te olvidó que no puede haber padre sin hijo

porque la trinidad es por definición un condicional?

¿Puedes decirme por qué, si no truco por ser en marco

necesariamente idiota, gotean culpa tus palabras

estancando agua en charcas que ni puedes ni sabes por qué limpiar,

siempre que no finges ser quien nunca ha estado

o bien que no recuerdas algo visto

con que atacar a quien has apresado por serte necesario

para que otros puedan creerte?

¿Y aún así te atreves mirar directo a unos ojos

para parasíticamete regar que estarás siempre viva?

Morirás. Es lo que ocurre.

¿Y?

Si estás viva, tienes alma.

Estás viva.

Dá lo mismo cómo.

Morirás. Es lo que ocurre.

¿Y?

Recuerda el lazo condicional.

No resucitarás ni me resucitarás,

ni te resucitarán, ni serás eterna

ni llegarás al tiempo siendo la suma tus posesiones,

y dá lo mismo si temporalidad es tu único hacer;

es lo que hace; o sea, tienes alma.

Yo también tengo una.

¡La mía hace lo mismo

y nada más!

Estoy vivo; morir es de ambos.

¿Y?

Es lo que ocurre. Estás viva

porque morirás; es la definición. Eres alma

porque estás viva porque morirás;

dá lo mismo si no saborearás la muerte

- o si la saboreas. Son detallismos. Morirás;

eres alma. Deja de joder.

Todo cuanto sabe tanto;

es obvio. Acéptalo,

y deja de joder;

nos tienes a todos hartos

con tu orgasmia fantasmagórica.

Location:

Antarctica

26.5.18

Song Of Myself, XXXIII, by Walt Whitman

|

Being wise cannot be hidden

the same as being simpleminded.

|

Space and Time! now I see it is true, what I guess’d at,

What I guess’d when I loaf’d on the grass,

What I guess’d while I lay alone in my bed,

And again as I walk’d the beach under the paling stars of the morning.

My ties and ballasts leave me, my elbows rest in sea-gaps,

I skirt sierras, my palms cover continents,

I am afoot with my vision.

By the city’s quadrangular houses—in log huts, camping with lumbermen,

Along the ruts of the turnpike, along the dry gulch and rivulet bed,

Weeding my onion-patch or hoeing rows of carrots and parsnips, crossing savannas, trailing in forests,

Prospecting, gold-digging, girdling the trees of a new purchase,

Scorch’d ankle-deep by the hot sand, hauling my boat down the shallow river,

Where the panther walks to and fro on a limb overhead, where the buck turns furiously at the hunter,

Where the rattlesnake suns his flabby length on a rock, where the otter is feeding on fish,

Where the alligator in his tough pimples sleeps by the bayou,

Where the black bear is searching for roots or honey, where the beaver pats the mud with his paddle-shaped tail;

Over the growing sugar, over the yellow-flower’d cotton plant, over the rice in its low moist field,

Over the sharp-peak’d farm house, with its scallop’d scum and slender shoots from the gutters,

Over the western persimmon, over the long-leav’d corn, over the delicate blue-flower flax,

Over the white and brown buckwheat, a hummer and buzzer there with the rest,

Over the dusky green of the rye as it ripples and shades in the breeze;

Scaling mountains, pulling myself cautiously up, holding on by low scragged limbs,

Walking the path worn in the grass and beat through the leaves of the brush,

Where the quail is whistling betwixt the woods and the wheat-lot,

Where the bat flies in the Seventh-month eve, where the great gold-bug drops through the dark,

Where the brook puts out of the roots of the old tree and flows to the meadow,

Where cattle stand and shake away flies with the tremulous shuddering of their hides,

Where the cheese-cloth hangs in the kitchen, where andirons straddle the hearth-slab, where cobwebs fall in festoons from the rafters;

Where trip-hammers crash, where the press is whirling its cylinders,

Wherever the human heart beats with terrible throes under its ribs,

Where the pear-shaped balloon is floating aloft, (floating in it myself and looking composedly down,)

Where the life-car is drawn on the slip-noose, where the heat hatches pale-green eggs in the dented sand,

Where the she-whale swims with her calf and never forsakes it,

Where the steam-ship trails hind-ways its long pennant of smoke,

Where the fin of the shark cuts like a black chip out of the water,

Where the half-burn’d brig is riding on unknown currents,

Where shells grow to her slimy deck, where the dead are corrupting below;

Where the dense-starr’d flag is borne at the head of the regiments,

Approaching Manhattan up by the long-stretching island,

Under Niagara, the cataract falling like a veil over my countenance,

Upon a door-step, upon the horse-block of hard wood outside,

Upon the race-course, or enjoying picnics or jigs or a good game of base-ball,

At he-festivals, with blackguard gibes, ironical license, bull-dances, drinking, laughter,

At the cider-mill tasting the sweets of the brown mash, sucking the juice through a straw,

At apple-peelings wanting kisses for all the red fruit I find,

At musters, beach-parties, friendly bees, huskings, house-raisings;

Where the mocking-bird sounds his delicious gurgles, cackles, screams, weeps,

Where the hay-rick stands in the barn-yard, where the dry-stalks are scatter’d, where the brood-cow waits in the hovel,

Where the bull advances to do his masculine work, where the stud to the mare, where the cock is treading the hen,

Where the heifers browse, where geese nip their food with short jerks,

Where sun-down shadows lengthen over the limitless and lonesome prairie,

Where herds of buffalo make a crawling spread of the square miles far and near,

Where the humming-bird shimmers, where the neck of the long-lived swan is curving and winding,

Where the laughing-gull scoots by the shore, where she laughs her near-human laugh,

Where bee-hives range on a gray bench in the garden half hid by the high weeds,

Where band-neck’d partridges roost in a ring on the ground with their heads out,

Where burial coaches enter the arch’d gates of a cemetery,

Where winter wolves bark amid wastes of snow and icicled trees,

Where the yellow-crown’d heron comes to the edge of the marsh at night and feeds upon small crabs,

Where the splash of swimmers and divers cools the warm noon,

Where the katy-did works her chromatic reed on the walnut-tree over the well,

Through patches of citrons and cucumbers with silver-wired leaves,

Through the salt-lick or orange glade, or under conical firs,

Through the gymnasium, through the curtain’d saloon, through the office or public hall;

Pleas’d with the native and pleas’d with the foreign, pleas’d with the new and old,

Pleas’d with the homely woman as well as the handsome,

Pleas’d with the quakeress as she puts off her bonnet and talks melodiously,

Pleas’d with the tune of the choir of the whitewash’d church,

Pleas’d with the earnest words of the sweating Methodist preacher, impress’d seriously at the camp-meeting;

Looking in at the shop-windows of Broadway the whole forenoon, flatting the flesh of my nose on the thick plate glass,

Wandering the same afternoon with my face turn’d up to the clouds, or down a lane or along the beach,

My right and left arms round the sides of two friends, and I in the middle;

Coming home with the silent and dark-cheek’d bush-boy, (behind me he rides at the drape of the day,)

Far from the settlements studying the print of animals’ feet, or the moccasin print,

By the cot in the hospital reaching lemonade to a feverish patient,

Nigh the coffin’d corpse when all is still, examining with a candle;

Voyaging to every port to dicker and adventure,

Hurrying with the modern crowd as eager and fickle as any,

Hot toward one I hate, ready in my madness to knife him,

Solitary at midnight in my back yard, my thoughts gone from me a long while,

Walking the old hills of Judæa with the beautiful gentle God by my side,

Speeding through space, speeding through heaven and the stars,

Speeding amid the seven satellites and the broad ring, and the diameter of eighty thousand miles,

Speeding with tail’d meteors, throwing fire-balls like the rest,

Carrying the crescent child that carries its own full mother in its belly,

Storming, enjoying, planning, loving, cautioning,

Backing and filling, appearing and disappearing,

I tread day and night such roads.

I visit the orchards of spheres and look at the product,

And look at quintillions ripen’d and look at quintillions green.

I fly those flights of a fluid and swallowing soul,

My course runs below the soundings of plummets.

I help myself to material and immaterial,

No guard can shut me off, no law prevent me.

I anchor my ship for a little while only,

My messengers continually cruise away or bring their returns to me.

I go hunting polar furs and the seal, leaping chasms with a pike-pointed staff, clinging to topples of brittle and blue.

I ascend to the foretruck,

I take my place late at night in the crow’s-nest,

We sail the arctic sea, it is plenty light enough,

Through the clear atmosphere I stretch around on the wonderful beauty,

The enormous masses of ice pass me and I pass them, the scenery is plain in all directions,

The white-topt mountains show in the distance, I fling out my fancies toward them,

We are approaching some great battle-field in which we are soon to be engaged,

We pass the colossal outposts of the encampment, we pass with still feet and caution,

Or we are entering by the suburbs some vast and ruin’d city,

The blocks and fallen architecture more than all the living cities of the globe.

I am a free companion, I bivouac by invading watchfires,

I turn the bridegroom out of bed and stay with the bride myself,

I tighten her all night to my thighs and lips.

My voice is the wife’s voice, the screech by the rail of the stairs,

They fetch my man’s body up dripping and drown’d.

I understand the large hearts of heroes,

The courage of present times and all times,

How the skipper saw the crowded and rudderless wreck of the steam-ship, and Death chasing it up and down the storm,

How he knuckled tight and gave not back an inch, and was faithful of days and faithful of nights,

And chalk’d in large letters on a board, Be of good cheer, we will not desert you;

How he follow’d with them and tack’d with them three days and would not give it up,

How he saved the drifting company at last,

How the lank loose-gown’d women look’d when boated from the side of their prepared graves,

How the silent old-faced infants and the lifted sick, and the sharp-lipp’d unshaved men;

All this I swallow, it tastes good, I like it well, it becomes mine,

I am the man, I suffer’d, I was there.

The disdain and calmness of martyrs,

The mother of old, condemn’d for a witch, burnt with dry wood, her children gazing on,

The hounded slave that flags in the race, leans by the fence, blowing, cover’d with sweat,

The twinges that sting like needles his legs and neck, the murderous buckshot and the bullets,

All these I feel or am.

I am the hounded slave, I wince at the bite of the dogs,

Hell and despair are upon me, crack and again crack the marksmen,

I clutch the rails of the fence, my gore dribs, thinn’d with the ooze of my skin,

I fall on the weeds and stones,

The riders spur their unwilling horses, haul close,

Taunt my dizzy ears and beat me violently over the head with whip-stocks.

Agonies are one of my changes of garments,

I do not ask the wounded person how he feels, I myself become the wounded person,

My hurts turn livid upon me as I lean on a cane and observe.

I am the mash’d fireman with breast-bone broken,

Tumbling walls buried me in their debris,

Heat and smoke I inspired, I heard the yelling shouts of my comrades,

I heard the distant click of their picks and shovels,

They have clear’d the beams away, they tenderly lift me forth.

I lie in the night air in my red shirt, the pervading hush is for my sake,

Painless after all I lie exhausted but not so unhappy,

White and beautiful are the faces around me, the heads are bared of their fire-caps,

The kneeling crowd fades with the light of the torches.

Distant and dead resuscitate,

They show as the dial or move as the hands of me, I am the clock myself.

I am an old artillerist, I tell of my fort’s bombardment,

I am there again.

Again the long roll of the drummers,

Again the attacking cannon, mortars,

Again to my listening ears the cannon responsive.

I take part, I see and hear the whole,

The cries, curses, roar, the plaudits for well-aim’d shots,

The ambulanza slowly passing trailing its red drip,

Workmen searching after damages, making indispensable repairs,

The fall of grenades through the rent roof, the fan-shaped explosion,

The whizz of limbs, heads, stone, wood, iron, high in the air.

Again gurgles the mouth of my dying general, he furiously waves with his hand,

He gasps through the clot Mind not me—mind—the entrenchments.

Labels:

alive,

Awake,

best poems of all time,

best poetry of all time,

Courage,

Death,

Dying,

free verse,

Living,

poem,

poems,

Poet,

poetry,

Poets,

purpose of poetry,

vitalism,

Walt Whitman

Location:

New York, NY, USA

26.2.18

I Know, You Walk--

by Hermann Hesse

I walk so often, late, along the streets,

Lower my gaze, and hurry, full of dread,

Suddenly, silently, you still might rise

And I would have to gaze on all your grief

With my own eyes,

While you demand your happiness, that's dead.

I know, you walk beyond me, every night,

With a coy footfall, in a wretched dress

And walk for money, looking miserable!

Your shoes gather God knows what ugly mess,

The wind plays in your hair with lewd delight---

You walk, and walk, and find no home at all.

|

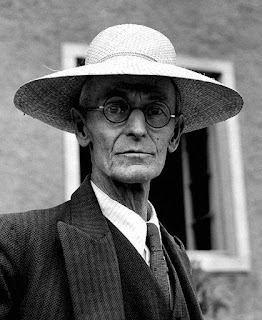

Born in the German Empire, when the Germans had no empire, Hesse didn't win the 1946 Nobel Prize in Literature for his fashion sense. Looks good though! |

I walk so often, late, along the streets,

Lower my gaze, and hurry, full of dread,

Suddenly, silently, you still might rise

And I would have to gaze on all your grief

With my own eyes,

While you demand your happiness, that's dead.

I know, you walk beyond me, every night,

With a coy footfall, in a wretched dress

And walk for money, looking miserable!

Your shoes gather God knows what ugly mess,

The wind plays in your hair with lewd delight---

You walk, and walk, and find no home at all.

25.8.16

as freedom is a breakfastfood

by e. e. cummings

as freedom is a breakfastfood

or truth can live with right and wrong

or molehills are from mountains made

—long enough and just so long

will being pay the rent of seem

and genius please the talentgang

and water most encourage flame

as hatracks into peachtrees grow

or hopes dance best on bald men’s hair

and every finger is a toe

and any courage is a fear

—long enough and just so long

will the impure think all things pure

and hornets wail by children stung

or as the seeing are the blind

and robins never welcome spring

nor flatfolk prove their world is round

nor dingsters die at break of dong

and common’s rare and millstones float

—long enough and just so long

tomorrow will not be too late

worms are the words but joy’s the voice

down shall go which and up come who

breasts will be breasts thighs will be thighs

deeds cannot dream what dreams can do

—time is a tree(this life one leaf)

but love is the sky and i am for you

just so long and long enough

--------

You may also enjoy these other poems by Edward Estlin Cummings:

|

E.E. Cummings dressed in his First World War military

uniform. WWI was far more psychologically damaging

than the Second World War or, arguably, any other war since

because it was fought in packed trenches with little to no territorial

gains or losses as a result of the introduction of machine guns

and the blatant, constant use of chemical weapons, specifically

mustard gas. Near the end of the war, roaring, mammoth-like

tanks appeared on the battlefields, steamrolling barbwire

and plowing over trenches. Even though the weaponry

mounted on the original tanks wasn't very effective, the psychological effect upon morale was significant in virtue of the loud rumble of their engines, their seeming disregard for infantry fire, not to mention their sheer size and the fact that most had never seen one before. With enemy infantry charging behind the tanks, shielded, the ensuing disarray was often enough to lead to an onslaught. The nickname The War to End All Wars owes its existence to the inhumane gruesomeness of the conflict. In the end, however, WWI wasn't won via territorial gains, but rather by a flanking strategy that successfully cut-off the supply lines pivotal to the survival of frontline troops of Germany and the Austria-Hungary Empire. Edward Estlin Cummings' palpable zest and love of life is the result of having experienced one of the most terrifying chapters in human history. For more information on the Era and its impact on Cumming's poetry, read "since feeling is first" and the accompanying essay. |

as freedom is a breakfastfood

or truth can live with right and wrong

or molehills are from mountains made

—long enough and just so long

will being pay the rent of seem

and genius please the talentgang

and water most encourage flame

as hatracks into peachtrees grow

or hopes dance best on bald men’s hair

and every finger is a toe

and any courage is a fear

—long enough and just so long

will the impure think all things pure

and hornets wail by children stung

or as the seeing are the blind

and robins never welcome spring

nor flatfolk prove their world is round

nor dingsters die at break of dong

and common’s rare and millstones float

—long enough and just so long

tomorrow will not be too late

worms are the words but joy’s the voice

down shall go which and up come who

breasts will be breasts thighs will be thighs

deeds cannot dream what dreams can do

—time is a tree(this life one leaf)

but love is the sky and i am for you

just so long and long enough

--------

For a review of the background to the life, poetic style, and historical context that shaped E. E. Cummings' exceptional body of work, please read the brief essay immediately after the following poem—

----------

You may also enjoy these other poems by Edward Estlin Cummings:

Labels:

Asleep,

Awake,

best poems of all time,

Cummings,

emotion,

Fear,

genius,

human condition,

Life,

Living,

love,

Mindfulness,

purpose of poetry,

Self-Actualization,

Self-Realization,

soul,

vitalism

Location:

Boston, MA, USA

23.10.15

Ressentiment in the Present Age, by Søren Kierkegaard

Excerpt from - Søren Kierkegaard, The Present Age, translated by Alexander Dru with Foreword by Walter Kaufmann, 1962, pp. 49–52.

It is a fundamental truth of human nature that man is incapable of remaining permanently on the heights, of continuing to admire anything. Human nature needs variety. Even in the most enthusiastic ages people have always liked to joke enviously about their superiors. That is perfectly in order and is entirely justifiable so long as after having laughed at the great they can once more look upon them with admiration; otherwise the game is not worth the candle. In that way ressentiment finds an outlet even in an enthusiastic age. And as long as an age, even though less enthusiastic, has the strength to give ressentiment its proper character and has made up its mind what its expression signifies, ressentiment has its own, though dangerous importance. […]

The more reflection gets the upper hand and thus makes people indolent, the more dangerous ressentiment becomes, because it no longer has sufficient character to make it conscious of its significance. Bereft of that character reflection is a cowardly and vacillating, and according to circumstances interprets the same thing in a variety of ways. It tries to treat it as a joke, and if that fails, to regard it as an insult, and when that fails, to dismiss it as nothing at all; or else it will treat the thing as a witticism, and if that fails, then say that it was meant as a moral satire deserving attention, and if that does not succeed, add that it was not worth bothering about. [...]

Ressentiment becomes the constituent principle of want of character, which from utter wretchedness tries to sneak itself a position, all the time safeguarding itself by conceding that it is less than nothing. The ressentiment which results from want of character can never understand that eminent distinction really is distinction. Neither does it understand itself by recognizing distinction negatively (as in the case of ostracism) but wants to drag it down, wants to belittle it so that it really ceases to be distinguished. And ressentiment not only defends itself against all existing forms of distinction but against that which is still to come.

The ressentiment which is establishing itself is the process of leveling, and while a passionate age storms ahead setting up new things and tearing down old, raising and demolishing as it goes, a reflective and passionless age does exactly the contrary; it hinders and stifles all action; it levels. Leveling is a silent, mathematical, and abstract occupation which shuns upheavals. In a burst of momentary enthusiasm people might, in their despondency, even long for a misfortune in order to feel the powers of life, but the apathy which follows is no more helped by a disturbance than an engineer leveling a piece of land. At its most violent a rebellion is like a volcanic eruption and drowns every other sound. At its maximum the leveling process is a deathly silence in which one can hear one’s own heart beat, a silence which nothing can pierce, in which everything is engulfed, powerless to resist.

One man can be at the head a rebellion, but no one can be at the head of the leveling process alone, for in that case he would be leader and would thus escape being leveled. Each individual within his own little circle can co-operate in the leveling, but it is an abstract power, and the leveling process is the victory of abstraction over the individual. The leveling process in modern times, corresponds, in reflection, to fate in antiquity. The dialectic of ancient times tended towards leadership (the great man over the masses and the free man over the slave); the dialectic of Christianity tends, at least until now, towards representation (the majority views itself in the representative, and is liberated in the knowledge that it is represented in that representative, in a kind of self-knowledge); the dialectic of the present age tends towards equality, and its most consequent but false result is leveling, as the negative unity of the negative relationship between individuals.

It must be obvious to everyone that the profound significance of the leveling process lies in the fact that it means the predominance of the category ‘generation’ over the category ‘individuality’.

---------

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like:

20.7.15

love is more thicker than forget

by E. E. Cummings

love is more thicker than forget

more thinner than recall

more seldom than a wave is wet

more frequent than to fail

it is most mad and moonly

and less it shall unbe

than all the sea which only

is deeper than the sea

love is less always than to win

less never than alive

less bigger than the least begin

less littler than forgive

it is most sane and sunly

and more it cannot die

than all the sky which only

is higher than the sky

--------

You may also enjoy these other poems by Edward Estlin Cummings:

|

| e.e. cummings enjoys a cigarette with the characteristic stare of someone who loves life and, therefore, living. Hades will have a hard time ever finding this man, :) |

love is more thicker than forget

more thinner than recall

more seldom than a wave is wet

more frequent than to fail

it is most mad and moonly

and less it shall unbe

than all the sea which only

is deeper than the sea

love is less always than to win

less never than alive

less bigger than the least begin

less littler than forgive

it is most sane and sunly

and more it cannot die

than all the sky which only

is higher than the sky

--------

For a review of the background to the life, poetic style, and historical context that shaped E. E. Cummings' exceptional body of work, please read the brief essay immediately after the following poem—

----------

You may also enjoy these other poems by Edward Estlin Cummings:

Labels:

best poems of all time,

Cummings,

Dying,

e.e. cummings,

Edward Estlin Cummings,

emotion,

empathy,

Life,

Living,

love,

love poetry,

modernism,

Relationships,

Semantics,

vitalism

Location:

Edinburgh, UK

7.7.15

The transmutation of the human spirit, by Friedrich Nietzsche

From Thus Spake Zarathustra, "The Three Metamorphoses"

Three metamorphoses of the spirit do I designate to you: how the spirit

becometh a camel, the camel a lion, and the lion at last a child.

Many heavy things are there for the spirit, the strong load-bearing

spirit in which reverence dwelleth: for the heavy and the heaviest

longeth its strength.

What is heavy? so asketh the load-bearing spirit; then kneeleth it down

like the camel, and wanteth to be well laden.

What is the heaviest thing, ye heroes? asketh the load-bearing spirit,

that I may take it upon me and rejoice in my strength.

Is it not this: To humiliate oneself in order to mortify one's pride? To

exhibit one's folly in order to mock at one's wisdom?

Or is it this: To desert our cause when it celebrateth its triumph? To

ascend high mountains to tempt the tempter?

Or is it this: To feed on the acorns and grass of knowledge, and for the

sake of truth to suffer hunger of soul?

Or is it this: To be sick and dismiss comforters, and make friends of

the deaf, who never hear thy requests?

Or is it this: To go into foul water when it is the water of truth, and

not disclaim cold frogs and hot toads?

Or is it this: To love those who despise us, and give one's hand to the

phantom when it is going to frighten us?

All these heaviest things the load-bearing spirit taketh upon itself:

and like the camel, which, when laden, hasteneth into the wilderness, so

hasteneth the spirit into its wilderness.

But in the loneliest wilderness happeneth the second metamorphosis: here

the spirit becometh a lion; freedom will it capture, and lordship in its

own wilderness.

Its last Lord it here seeketh: hostile will it be to him, and to its

last God; for victory will it struggle with the great dragon.

What is the great dragon which the spirit is no longer inclined to call

Lord and God? "Thou-shalt," is the great dragon called. But the spirit

of the lion saith, "I will."

"Thou-shalt," lieth in its path, sparkling with gold--a scale-covered

beast; and on every scale glittereth golden, "Thou shalt!"

The values of a thousand years glitter on those scales, and

thus speaketh the mightiest of all dragons: "All the values of

things--glitter on me.

All values have already been created, and all created values--do I

represent. Verily, there shall be no 'I will' any more. Thus speaketh

the dragon.

My brethren, wherefore is there need of the lion in the spirit? Why

sufficeth not the beast of burden, which renounceth and is reverent?

To create new values--that, even the lion cannot yet accomplish: but to

create itself freedom for new creating--that can the might of the lion

do.

To create itself freedom, and give a holy Nay even unto duty: for that,

my brethren, there is need of the lion.

To assume the right to new values--that is the most formidable

assumption for a load-bearing and reverent spirit. Verily, unto such a

spirit it is preying, and the work of a beast of prey.

As its holiest, it once loved "Thou-shalt": now is it forced to find

illusion and arbitrariness even in the holiest things, that it may

capture freedom from its love: the lion is needed for this capture.

But tell me, my brethren, what the child can do, which even the lion

could not do? Why hath the preying lion still to become a child?

Innocence is the child, and forgetfulness, a new beginning, a game, a

self-rolling wheel, a first movement, a holy Yea.

Aye, for the game of creating, my brethren, there is needed a holy Yea

unto life: ITS OWN will, willeth now the spirit; HIS OWN world winneth

the world's outcast.

Three metamorphoses of the spirit have I designated to you: how the

spirit became a camel, the camel a lion, and the lion at last a child.--

Thus spake Zarathustra. And at that time he abode in the town which is

called The Pied Cow.

------------

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like:

Three metamorphoses of the spirit do I designate to you: how the spirit

becometh a camel, the camel a lion, and the lion at last a child.

Many heavy things are there for the spirit, the strong load-bearing

spirit in which reverence dwelleth: for the heavy and the heaviest

longeth its strength.

What is heavy? so asketh the load-bearing spirit; then kneeleth it down

like the camel, and wanteth to be well laden.

What is the heaviest thing, ye heroes? asketh the load-bearing spirit,

that I may take it upon me and rejoice in my strength.

Is it not this: To humiliate oneself in order to mortify one's pride? To

exhibit one's folly in order to mock at one's wisdom?

Or is it this: To desert our cause when it celebrateth its triumph? To

ascend high mountains to tempt the tempter?

Or is it this: To feed on the acorns and grass of knowledge, and for the

sake of truth to suffer hunger of soul?

Or is it this: To be sick and dismiss comforters, and make friends of

the deaf, who never hear thy requests?

Or is it this: To go into foul water when it is the water of truth, and

not disclaim cold frogs and hot toads?

Or is it this: To love those who despise us, and give one's hand to the

phantom when it is going to frighten us?

All these heaviest things the load-bearing spirit taketh upon itself:

and like the camel, which, when laden, hasteneth into the wilderness, so

hasteneth the spirit into its wilderness.

But in the loneliest wilderness happeneth the second metamorphosis: here

the spirit becometh a lion; freedom will it capture, and lordship in its

own wilderness.

Its last Lord it here seeketh: hostile will it be to him, and to its

last God; for victory will it struggle with the great dragon.

What is the great dragon which the spirit is no longer inclined to call

Lord and God? "Thou-shalt," is the great dragon called. But the spirit

of the lion saith, "I will."

"Thou-shalt," lieth in its path, sparkling with gold--a scale-covered

beast; and on every scale glittereth golden, "Thou shalt!"

The values of a thousand years glitter on those scales, and

thus speaketh the mightiest of all dragons: "All the values of

things--glitter on me.

All values have already been created, and all created values--do I

represent. Verily, there shall be no 'I will' any more. Thus speaketh

the dragon.

My brethren, wherefore is there need of the lion in the spirit? Why

sufficeth not the beast of burden, which renounceth and is reverent?

To create new values--that, even the lion cannot yet accomplish: but to

create itself freedom for new creating--that can the might of the lion

do.

To create itself freedom, and give a holy Nay even unto duty: for that,

my brethren, there is need of the lion.

To assume the right to new values--that is the most formidable

assumption for a load-bearing and reverent spirit. Verily, unto such a

spirit it is preying, and the work of a beast of prey.

As its holiest, it once loved "Thou-shalt": now is it forced to find

illusion and arbitrariness even in the holiest things, that it may

capture freedom from its love: the lion is needed for this capture.

But tell me, my brethren, what the child can do, which even the lion

could not do? Why hath the preying lion still to become a child?

Innocence is the child, and forgetfulness, a new beginning, a game, a

self-rolling wheel, a first movement, a holy Yea.

Aye, for the game of creating, my brethren, there is needed a holy Yea

unto life: ITS OWN will, willeth now the spirit; HIS OWN world winneth

the world's outcast.

Three metamorphoses of the spirit have I designated to you: how the

spirit became a camel, the camel a lion, and the lion at last a child.--

Thus spake Zarathustra. And at that time he abode in the town which is

called The Pied Cow.

------------

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like:

4.7.15

since feeling is first, by e.e. cummings

since feeling is first

who pays any attention to the syntax of things

will never wholly kiss you;

wholly to be a fool

while Spring is in the world

my blood approves,

and kisses are better fate

than wisdom

lady i swear by all flowers. Don't cry

-the best gesture of my brain is less than

your eyelids' flutter which says

we are for each other: then

laugh, leaning back in my arms

for life's not a paragraph

And death i think is no parenthesis

-----

Originally published in is 5 by E. E. Cummings. Since it isn't public domain yet, you can read about half of the poems contained therein by clicking here.

-----

e.e. cummings (without capital letters as he did not like capital letters much) was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on October 14, 1894. He died on September 3, 1962, being the second most widely read poets in the United States after Robert Frost [read some of his poems], as great a poet and wonderful counterpart precisely because they almost represent polar opposites insofar as style, tone and thematic content.

After completing undergraduate studies and a Masters of Arts at Harvard University by 1916, Edward Estlin Cummings enlisted as a volunteer ambulance driver during World War I. Five months later, he was detained on suspicion of espionage by French authorities. The consistent and constant vitalist message in his poetry, his enduring love of life, is likely a product of having witnessed the "War to End All Wars".

Of course, the "War to End All Wars" did not end all wars and, in fact, led to an even deadlier and longer one, World War II, only two decades later. However, contrary to popular belief, World War I was far more gruesome for participants than was WWII. The reason for this is largely technological. On the one hand, airplanes were still too basic to provide any decisive advantage, and tanks only came into existence near the end of that war, invented by the English and quickly replicated by everyone else, but these were too few, clunky and slow to permit the quick troop movements seen during the Second World War.

On the other hand, the machine gun had been perfected and great strides had been made in artillery, mortars, and in chemical warfare, particularly mustard gas, against which early gas masks afforded little protection.

The result was that the First World War was largely a trench war that was basically a stalemate where troops would advance with many losses from one trench to the next only to have a counterattack drive them back from that trench to where they had come from. The use of toxic gas had two purposes: not only did it provide a cloud of cover that impeded proper aiming by machine guns, it also killed or severely injured the troops holed up in the trench that was being advanced towards.

|

| Photograph of World War I infantrymen spending their days in trenches covered by sandbags and protected by barbed wire. |

The First World War only ended because the Allied Powers managed to successfully flank the Central Power's trench lines, cutting off their front line troops from receiving supplies. This maneuver led to a Conditional Surrender or Capitulation by the Central Powers (i.e., Germany, the Austria-Hungary Empire, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), unlike the end of World War II which was concluded in an Unconditional Surrender.

|

| World map of the Allied Powers, the Central Powers, and their colonies, at the onset of World War I. Allies shown in green; Central Powers shown in orange, and neutral territories are displayed in gray. Russia withdrew from the war in 1917, ceding the territories the Central Powers had managed to occupy following the Bolshevik Revolution and their need to focus on internal affairs as their new state restructured. The United Socialist Soviet Republics would get back control over these territories following World War II. |

The conditions set by the Allied Powers (i.e., the British Empire, France, Italy, and Japan) split the Austria-Hungary into two separate states, spelled the end of the Ottoman Empire, but the conditions were harshest against Germany, being considered the main culprit. These included large territorial transfers, of particular importance are Alsace-Lorraine going to France and most of Western Prussia going to the establishment of the nation of Poland. However, it was the large economic reparations imposed on Germany that led to its economic collapse soon afterwards and allowed the Nazi Party's rise to power. Not surprisingly, one of Hitler's first orders of business was to violate the Treaty of Versailles via a surprise re-militarization in 1936 of the Rhineland; moreover, the German invasion of Poland on September 1939 marks the beginning of the Second World War. Allied cowardice permitted it all, and Hitler would later say "If France had then marched into Rhineland, we would have had to withdraw with our tail between our legs", a hypothetical event that would have likely prevented WWII altogether because the French army was still overwhelmingly larger and better equipped than Germany's given that the latter had just begun the rebuilding of their military strength.

|

| Click to Enlarge. German territory at onset of World War I and the remaining territory at the end of World War II, in gray at top, in blue at bottom. The reunification of Germany did not occur until 1990, following the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall. |

History aside, the psychological effects of the dehumanizing nature of World War I and the mass and unusually cruel deaths that were everyone to be seen had a profound influence on e.e. cummings' celebration of life, living, and the vitality in all of us that most people either hinder or ignore.

|

| Otto Dix (1924) "Shock Troops Advance under Gas". Otto Dix participated in what is known as Germany's cultural Golden Age during the decade of the 1920s. |

----------

Read more poems by Edward Estlin Cummings.

Labels:

alive,

Awake,

best poems of all time,

Cummings,

Death,

Dying,

e.e. cummings,

Edward Estlin Cummings,

ethics,

is5,

Living,

love,

modernism,

morality,

vitalism,

War,

wisdom

Location:

Chicago, IL, USA

24.5.15

now does our world descend, by e.e. cummings

now does our world descend

the path to nothingness

(cruel now cancels kind:

friends turn to enemies)

therefore lament,my dream

and don a doer's doom

create now is contrive;

imagined,merely know

(freedom:what makes a slave)

therefore,my life,lie down

and more by most endure

all that you never were

hide,poor dishonoured mind

who thought yourself so wise;

and much could understand

concerning no and yes:

if they've become the same

it's time you unbecame

where climbing was and bright

is darkness and to fall

(now wrong's the only right

since brave are cowards all)

therefore despair,my heart

and die into the dirt

but from this endless end

of briefer each our bliss -

where seeing eyes go blind

(where lips forget to kiss)

where everything's nothing

- arise,my soul;and sing

--------

For an informative background of the life, style, and historical context encasing e.e. cummings' exceptional body of work, please read the article immediately after the following poem—

You may also enjoy these other poems by Edward Estlin Cummings:

Labels:

best poems of all time,

Courage,

Death,

Dying,

e.e. cummings,

Edward Estlin Cummings,

ethics,

excellence,

Fear,

Life,

Living,

modernism,

morality,

morals,

poem,

poetry,

Self-Actualization,

Self-Realization,

vitalism

Location:

Manhattan, New York, NY, USA

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Featured Original:

How You Know What You Know

In a now classic paper, Blakemore and Cooper (1970) showed that if a newborn cat is deprived of experiences with horizontal lines (i.e., ...

-

The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2) is the most comprehensive personality test currently available. Using 567 true or ...

-

Both the long and short forms of the MMPI-2 but not the MMPI-A commonly given to adolescents are available through this link . The Minne...